|

Stalag IX-B |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

AMERICAN PRISONERS OF WAR IN GERMANY

STALAG 9 B

--

BAD ORB, GERMANY LOCATION Stalag 9B was situated in the outskirts of Bad Orb (500 14” N. -9°22” E.) In the Hossan-Nassau region of Prussia. 51 kilometers northwest of Frankfurt-on-Main. STRENGTH On 17 Dec. 1944, 985 PW captured during the first 2 days of the German counter-offensive, were marched for 4 days from Belgium into Germany. During this march, they received food and water only once. The walking wounded received no attention except such first aid as American medical personnel in the column could give them. They reached Geroldstein and were packed into boxcars, 60 men to the car. The cars were so small that the men could not lie down. PW entered the cars on 21 Dec. and did not get out until 26 Dec. En route, they were fed only once. Eight men seeking to escape jumped into a field and were killed by an exploding land mine. The German sergeant in charge, enraged that anyone had attempted escape, began shooting wildy. Although he knew that every car was densely packed with PW, he fired a round through the door of a car, killing an American soldier. The day after Christmas, the men arrived at Bad Orb. On January 25 the camp reached its peak with 4,070 American enlisted men. The following day 1275 NCO’s were transferred to Stalag 9A, Ziegenhain. On 28 Feb 1,000 privates left 12A, Limburg, for Bad Orb. They marched in a column which averaged 25 miles a day. On leaving, they were given one-half a loaf of bread and a small cheese for the five-day march. No medical supplies were available; men who collapsed were left behind under guard. PW had no blankets and some had only a shirt and pair of trousers for clothing. Their arrival, plus that of other PW, brought the camp strength to 3,333 on 1 April 1945. DESCRIPTION From 290 to 500 PW were jammed into barracks of the usual one-story wood and tarpaper types, divided into 2 sections with a washroom in the middle. Washroom facilities consisted of one cold water tap and one latrine hole emptying into an adjacent cesspool which had to be shoveled out every few days. Each half of the barracks contained a stove. Throughout the winter the fuel ration was 2 arm loads of wood per stove per day, providing heat for only one hour a day. Bunks, when there were bunks, were triple-deckers arranged in groups of four. Three barracks were completely bare of bunks and two others had only half the number needed with the result that 1,500 men were sleeping on the floors. PW who were fortunate received one blanket each, yet at the camp’s liberation some 30 PW still lacked any covering whatsoever. To keep warm, men huddled together in groups of 3 and 4. All barracks were in a state of disrepair; roofs leaked; windows were broken; lighting was either unsatisfactory or lacking completely. Very few barracks had tables and chairs. Some bunks had mattresses and some barrack floors were covered with straw, which PW used in lieu of toilet paper. The outdoor latrines had some 40 seats, totally insufficient for the needs of 4,000 men. Every building was infested with bedbugs fleas, lice and other vermin. Pfc. J.C. F. Kasten was Man of Confidence, assisted by Pvt. Edmun Pfannenstiel who spoke German fluently. When Pfc. Kasten was sent out on a Commando working party, the barracks leaders suggested that Pvt. Pfannenstiel succeed him. Pvt. Pfannenstiel refused to take the post, however, until the barracks leaders had consulted PW in their charge and gained their approval. Subsequently, he was an extremely able MOC. His assistant was PFC. Ben F. Dodge. Other important members of the staff were:

GERMAN PERSONNEL Noteworthy members of the German complement are listed below:

It was Hauptmann Kuhle who permitted American PW to replace Russians in the camp kitchen and Pvt. Dathe who enabled them illegally to appropriate extra rations. Gefreiter Weiss, at great personal risk, informed the MOC as to the progress of the war and daily located the position of advancing American troops on maps which he smuggled into the American PW. After a 23 March 1945 visit the Swiss Delegate reported, “In spite of the fact that it is difficult to obtain any kind of material to improve conditions, it is most strongly felt that the camp commander with his staff have no interest whatsoever in the welfare of the prisoners of war. This is clearly shown by the fact that although he made many promises on our last visit, he has not even tried to ameliorate conditions and is apt to blame the Allies for these conditions due to their constant bombing.” TREATMENT In a report describing Stalags 9A, 9C, and 9B, which he visited 13 March 1945, the Representative of the International Red Cross stated, “The situation may be considered very serious. The personal impression which one gets from an inspection tour of these camps cannot be described. One discovers distress and famine in their most terrible forms. Most of the prisoners who have come here from the territories of the East, and those who still continue to come, are nothing but skin and bones. Very many of them are suffering from acute diarrhea with bloody phlegm due to their complete exhaustion. Pneumonia, dorsal and bronchial cases are very common. The prisoners who have been in camp for a long time are often also so thin that those whom one had known previously can hardly be recognized. These prisoners, in rags, covered with filth and infested with vermin, live crowded together in barracks, when they do not lie under tents, squeezed together on the ground on a thin pallet of dirty straw or 2 or 3 per cot, or on benches and tables. Some of them are scarcely able to get up, or else they fall in a swoon as they did when they tried to get up when the Representative was passing through. They do not move, even at meal time, when they are presented with their inadequate German rations (for example 9B has been completely without salt for weeks). FOOD When the Americans arrived the kitchen was in charge of Russian PW under the lax supervision of German guards. Sanitary conditions in the kitchen were foul and the soup prepared was practically inedible. When the MOC was permitted to substitute American PW for the Russian help, there resulted a considerable improvement in the preparation of the meager prison fare. The 8 bushels of potatoes which German Pvt. Dathe enabled the Americans to steal was most necessary since the German ration was terribly slight. It consisted of 300 grams of bread, 550 grams of potatoes, 30 grams of horse meat, one-half liter of tea and one-half liter of soup made from putrid greens. The greens made the men sick, and the MOC intervened to have the allotment of greens changed to oatmeal. Later, even this small ration was cut so that at the end of their stay PW were receiving only 210 grams of bread and 290 grams of potatoes per day. The MOC was convinced that a larger ration was available and attributes its non-distribution to Oberst Sieber, the commandant. The full ration listed above was the minimum German civilian ration minus fresh vegetables, eggs and whole milk. No German soldier was so ill fed. A thousand men lacked eating utensils of any kind - either spoons, forks or bowls. They ate out of their helmets or old tin cans or pails - anything on which they could put their hands. Only one shipment of Red Cross food parcels reached camp, 2,300 parcels on 10 March 1945. Failure of another shipment to arrive from Geneva was attributed to the chaotic transportation conditions within Germany. The German rations had a paper value of 1,400 calories. Actually, the caloric content was ~even further lowered by the waste in using products of inferior quality. Since a completely inactive man needs at least 1,700 calories to live, it is apparent that PWs were slowly starving to death. HEALTH In the month between 28 Feb. and 1 April, 32 Americans died of malnutrition and pneumonia. Medical attention was in the care of the 2 American medical officers and 10 American medical orderlies. On 23 March the infirmary held 72 patients, 22 of whom were pneumonia cases. The others suffered from malnutrition and dysentery. Influenza, grippe, and bronchitis were common throughout the camp. No medical parcels were received from the Red Cross and the extreme scarcity of medicines furnished by the Germans contributed to deaths of PW who otherwise might have been saved. The MOC considered it fortunate in light of the exposure, starvation and lack of medical facilities, that more PW did not die. CLOTHING Instead of issuing clothing, the Germans confiscated it from PW. Upon being captured many men were forced to give up everything they were not wearing, such extra items as shoes, overshoes, blankets and gloves. Some had only shirts and trousers, no jackets. Others lacked shoes and bundled their feet in rags. At Limburg and elsewhere en route from the front, Germans took American overcoats with the result that as late as the last week of March one-fifth of the PW had none. No clothing came from the Red Cross because of the transportation breakdown. WORK On 8 Feb. 350 of the physically fit PW were sent to a work detachment in the Leipzig district. Other men at the camp were forced to carry out the string housekeeping chores. Until Pvt. Pfannenstiel became MOC, German guards had marched into the camp and taken the first men in sight for necessary camp details. This resulted in considerable inequity since they not infrequently took the same men time after time. The MOC arranged to take care of all details through men physically fit to work and subsequently furnished a daily work roster to the Germans. PAY In Dec. 1944 en route to Bad Orb, PW were lined up at Waxweiler and forced to give up all money in their possession. About $10,000 was taken from the 985 men by the German lieutenant in charge and no receipts given. Since the issue of “lagergeld” had been abolished, no money was paid to officer or NCO’s. The amount due them was credited by the Germans to their account every month. to be settled at the war’s end. Non-working privates received no pay. No incoming mail was received. The issue of letter-forms was irregular and haphazard, but each PW was permitted to mail home a form postcard informing Next-of-kin of his status. MORALE Morale fell rapidly under the brutalizing conditions and by March the majority of men were absolutely broken in spirit, crushed and apathetic. The Swiss delegate emphasized the fact that even American and British PW asked for food like beggars. WELFARE The Protecting Power inspectors visited the camp on 24 Jan. and 23 March 1945, each time reporting the atrocious camp conditions and extracting promises from the commandant. The International Red Cross representative wrote an extremely strong report decrying camp conditions as he saw them on 10 March 1945. That more Red Cross food and supplies did not reach camp must be attributed to the disruption of German transport. For similar reasons, the YMCA was never able to visit the camp nor to supply recreational equipment. RELIGION Until 25 Jan., no room was available for either Catholic or Protestant services, although 2 chaplains were present in the camp. In Feb., however, the chaplains held regular services for both denominations and received the cooperation of German camp authorities. When the MOC refused to single out Jews for segregation, a German Officer selected those American PW who he thought were Jews and put them in a separate barracks. No other discrimination was made against them. RECREATION From the end of December to the middle January, PW were allowed to leave the barracks only between 0630 and 1700 hours; the rest of the time they were locked in. Outdoor recreation was non-existent because of PW’s weakness. The British lazaret at Bad Soden sent over 32 books, the only volumes obtainable. PROPOSED EVACUATION Being informed of the rapid advance of the American forces, Pvt. Pfannenstiel began to prepare a camp organization to meet the contingencies of their arrival. Secretly, with the aid of the barrack leaders, he selected 500 of the most reliable men in the camp and made them military police, whose authority was to begin when the American troops arrived in the vicinity, at which time they were to maintain control and order within the camp. About the third week in March, the district commander ordered that 1 ,~00 of the men in Stalag 9B be marched eastward to another camp. When he received the order, subject protested that to march the men in their semi-starved condition was impossible. He realized that the Americans were close and wished to prevent the march by any means possible. The district commander met his protest by reducing the number demanded to 1,000. Subject was told to choose the 1,000 best fitted for the march. He then went to the German medical officer in charge of the camp and pointed out that there were a number of diphtheria and possibly typhus cases in the camp and that to march them off might spread an epidemic through the area covered by the march. He was successful in convincing the doctor who proceeded to slap a ten-day quarantine on the camp. By this means subject was able to prevent the movement of any of the American POW until they were rescued by American forces. LIBERATION Subject was attending church services in the camp at 1415 hours on Easter Sunday, 1 April 1945, when he was called out of the church. He suspected at this time that the Americans might be closing on the camp. Sent by the camp commander to Bad Orb, a hospital town, he was taken to the major in command of the town hospitals. The major proposed that subject take a white flag and proceed to meet the American troops and guarantee the surrender of the town. This proposal strongly accorded with the wishes of the townspeople. Subject felt that an American soldier wandering around alone behind German lines carrying a white flag might have some trouble so he refused to go unless he was accompanied by two unarmed German officers. The major named 2 officers and with them subject proceeded toward the edge of town. By this time an American unit, rumored to be one of great size and power, had occupied the hill overlooking the town. As subject’s party reached the edge of the town, it was stopped by the German, Major Fulkmann, charged with the military defense of the town. Fulkmann denied having made any arrangement with the medical major for its surrender and refused to permit the party to proceed until he had consulted with the medical major. At this time the German garrison opened up with small arms fire against the American position on the hill, and the Americans answered with machine guns. Subject’s party was caught between the two fires. The German officer with him then walked down the street and told him to follow and keep cool. In the meantime the American firing, which had starter high over his head, was getting lower and lower. Without much time to spare, the German officer and he managed to duck into an underground hospital. During the night the medical major and the major in command of the garrison met at the hospital to consult on what to do. In the meantime the Americans began firing artillery shells into the town. They dropped one shell regularly every 15 minutes. The medical major persuaded the garrison major that resistance was hopeless and the latter agreed to withdraw his troops. The withdrawal took place during the night and the next morning Pvt. Pfannenstiel’s party again went forward with their white flag to meet the Americans. They made contact on the edge of the town with Capt. Langley, commander of an American reconnaissance group of 200 men that had run 60 miles ahead of the main body of the American forces, and hours ahead of its own ammunition supply. By the time that the group entered Bad Orb with its tank guns and anti-tank weapons pointing fiercely in all directions, there was not a single round of artillery ammunition available to be fired from any of the guns. Subject borrowed a car and returned with some of the American soldiers to Stalag 9B. There everything was in order, the German guard unit remained and the camp commander turned over the control of the camp to the Americans. At about noon, American units of the main body began to pass through the town, and when they learned of the pitiful condition of the American Pws at Stalag 9B, the units, as they passed through, emptied their PX stores and sent them up to the prisoners. After several days, the American personnel at Stalag 9B were evacuated to Camp Lucky Strike near Le Havre, France. “SOURCE MATERIAL FOR THIS REPORT CONSISTED OF INTERROGATIONS OF FORMER PRISONERS OF WAR MADE BY CPM BRANCH, MILITARY INTELLIGENCE SERVICE, AND REPORTS OF THE PROTECTING POWER AND INTERNATIONAL RED CROSS RECEIVED BY THE STATE DEPARTMENT (Special War Problems Division).” Taken from the general introduction to camps. Scanned/Re-typed by John Kline 11/1996 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Yanks Weep as Third Army Rescues Them from Prison By Edward D. Bull Some of the 3,400 American soldiers set free when U. S. Third Army troops broke into their prison camp near Bad Orb, northeast of Hanay, were removed to France Wednesday in C-47 transport planes which landed on a former German airfield east of the Rhine. But many of the Americans were too weak from hunger and excitement to leave their bunks when the air evacuation began. The captive doughboys – gaunt, emaciated and deliriously happy – had been imprisoned since the battle of the Belgium bulge. They were among 6,500 prisoners of virtually all nationalities at war with German, including a Russian general and his staff, who were crowed into the filthy, stinking barracks of a stalag camp on a hill three miles outside of town. Most were from units overrun by the German Ardennes breakthrough which began December 16. All were privates except for a handful of officers. Most of the officers were moved from the Bad Orb weeks ago. The noncoms were taken to Ziegenhain recently and liberated there last week by units of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army. The hungry, hollow-cheeked Americans, many of them little more than skin and bones, said their prison diet had consisted of “grass soup”, whose ingredients they described at dehydrated carrots, cabbage and sticks and stones. Two dozen white crosses marked the graves of Yanks who had died while held at Bad Orb. “You should have seen these GI’s when we came int camp,” said Pfc. Clotis Pelfree of Bloomington, Ind., whose battalion prepared the Americans for their journey to France. “Some of them bawled like kids,” said Pelfree. “We started handing out cigarettes and they nearly mobbed us.” Sgt. Leonard

Fooshkill of Bernardsville, N. J. recognized a rifleman from his old

company among the prisoners. During their confinement, 140 men were jammed in barracks 100 feet long and 20 feet wide. “We were so crowded there wasn’t even room for everybody on the floor,” one prisoner said. “We had to sleep on top of one another. A latrine busted in our barracks but nobody was allowed to leave the building from sunset to dawn. “Cigarettes cost over $4 apiece. One man traded a $140 wrist watch for a package of American cigarettes.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The ID tag of Staff-Sergeant Matthew J. Schmidt of A Company, 2nd Tank Battalion, 9th US Armoured Division. Schmidt was captured during the Battle of the Bulge. Copyright: Bill Holland. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Stalag IX B By: Oren Windholz Stalag, short for the German word Stammiager, was a camp for Prisoners of War (Kriegsgefangener, shortened by the POWs to “Kriegie”) in German controlled lands. There were 42 of them primarily for captured ground forces. Additionally six camps held airmen, four held officers and one held naval POWs. The United States, Germany, Italy, France, and Great Britain all signed the agreement in Geneva in 1929 on treatment of prisoners. The Soviet Union refused to sign, insisting on the validity of an earlier agreement. Japan signed the agreement but it was not ratified in the homeland. Airmen and soldiers captured in the early stages of the invasion were considered a prize catch for the Germans for purposes of interrogation. During the Battle of the Bulge over 23,000 Americans were captured, causing a great logistical burden on Germany. This was nearly one fourth of all Americans captured. Chaos strained the crumbled food and transportation system in Germany in those final months of the war. French, Italians, Serbians, and Russians were at Stalag IX B when the American POWs arrived. Each nationality was separated by fence into compounds. The American total at one point reached over 4000 in late January and remained above 3000. American officers from regimental commander on down were transferred to Stalag XIII B at Hammulburg. Two medical, one dental and two clergy officers were left to minister to the prisoners. 1,263 non commissioned officers were transferred to Stalag IX A. An additional 1000 privates were sent into IX B in late February after a five-day march from Stalag XII at Limburg. Many were men captured in the Normandy battle. In early February 349 Americans were sent to the camp at Berga am Elster. The group included the American Chief Man of Confidence Hans Kasten, two assistants and all the American Jewish soldiers the Germans could identify. In the month before liberation, 45 British paratroopers were sent in to the American camp sector. Red Cross representatives and those who saw other camps considered IX B to be among the worst. Incredible over crowding, deplorable facilities and starvation diets were responsible, but perhaps also because the camp contained mostly American privates. Officers and airmen were known to have received better treatment. Facilities: The smaller barracks were wooden, holding about 160 men, divided by a center room with a water faucet and a latrine hole in the floor. Masonry barracks held several hundred men. Some 16 buildings in the compound housed Americans, a few dedicated for kitchen and other support services. An outdoor latrine had about 40 seats. Toilet paper was not issued. Men used handkerchiefs, wood excelsior or weeds in the mattresses according to Pete House. While on the train he was given a pocket book from another soldier. “This book was to be my personal toilet paper. To make it last, I finally began using pieces about 2 by 2 inches in size.” One day they were issued some sort of POW records that were printed on one side, which House made into a diary. The buildings, not made for winter use, were infested with lice, fecal material and other vermin. There were not enough beds and blankets for the men, particularly later arrivals, and nearly a third had to sleep on the floors. A stove was in each half of the barracks, but burned only an hour a day, which used up the wood allotment and did little to stave off the cold blowing in through broken windows and cracks between boards. Food: The constant meager rations resulted in part from the sheer inability of Germany to feed its own people. The Russians were in charge of the camp kitchen upon arrival of the Americans, who soon installed their own cooks by enlisting the cooperation of German guards. The Russian kitchen was unsanitary and the food was foul. There were no regular eating utensils, some were given a pail and “many [1000] men had to eat out of helmets.” Pete House said “as far a spoons and forks we were on our own.” He carved a spoon out of wood broken from his bunk. “Most used their fingers. At one time we were given a few combination fork and spoons made out of aluminum (result of an International Red Cross inspection). We had a drawing in my barracks and I won one. It was soon stolen.” The food was inadequate for daily needs and malnutrition was general. An “official ration” for each day existed but was never provided. Most days watery turnip or sugar beet soup, bread and a few potatoes were the mainstay. Potato peelings and castoffs from the Germans were thrown into a big pot for soup. A horse carcass, when available, was lowered into the boiling soup and the meat that fell into the soup was a treat. House said, “Every one wanted all the solids in the soup so the chant to the servers was to dig deep into the barrel.” A declassified report states, “The CMOC Pfannenstiel intervened to have the allotment of (putrid) greens changed to oatmeal.” A system pumped water to the camp for personal and cooking use. It was knocked out in March and water had to be carried up the mountain from the officers’ barracks. Men slowly starved to death. CMOC Pfannenstiel said “we [the staff] were given extra rations which we took to the infirmary to feed the boys.” The daily fight to survive drove men to steal food from camp storage and from each other. Two starving POWs broke into the camp kitchen, “took some foodstuff out of a cupboard and consumed it immediately.” They were surprised by the kitchen-bookkeeper. When he drew his pistol and summoned one of the men to leave his hiding place under the kitchen-table, the “other approached behind [the bookkeepers] back and hit him on the skull with the blunt end of a hatchet he had taken from the log of wood.” The German collapsed and “was beaten further 12 or 13 times.” The Germans went to the POW staff office and said if the two men were not found they would shoot 10 prisoners each hour. They ordered the Americans to stand out in the snow for hours under armed guard. When returned to the barracks there was no food, drink or firewood. Just before the deadline, one of the men reported himself to a chaplain. The two were arrested, jailed and courts martial proceedings initiated. The only Red Cross shipment, which arrived in mid March, probably saved many lives. The Americans shared it with the English. Other shipments were promised, but never arrived. Pfannenstiel recalled “it was good what we got, it kind of cheered the men up, but it was just like a drop in the bucket. There was very little, but what we got everybody enjoyed. That was the only thing we ever got.” Pete House said on February 14th, each four Americans received a Red Cross box, donated by the Serbian POWs. Earlier in the war, some prison camps received Red Cross packages every week and put on banquets on special holidays. Daily Life: Discipline was very strict and infractions more severely dealt with through January of 1945. “If they took our American prisoners out to cut down trees for firewood, they had German guards with them and watched them every step of the way, till they brought them back into the camp.” Camp rules provided for reporting of all infractions. The List of Serious Offenders cited 18 men for stealing plus the two men for attempted robbery and manslaughter. In February alone, over 100 men were listed in the Punishment Record for stealing other men’s possessions, stealing food, securing seconds, attempting to secure seconds and trading with the Russians or British. Punishment in January was confinement in the German guardhouse. Thereafter it was mostly latrine duty, bucket duty, restrictions, and warnings. Pete House said bucket duty was emptying the tanks under the barracks toilet. “Of course some of the stuff sloshed on these men and we had neither washing facilities nor spare clothes.” Punishment by the Germans was noted in the records by CMOC Pfarmenstiel to be “without sanction or approval of this official.” As the weeks passed the POW staff and barracks leaders operated more independently. This was in part due to greater diplomacy between the staff and the authorities. Reliable men were made MPs with duties such as watching for stealing when the potato wagon was unloaded. Conversely, however, general health, morale, and conditions declined. One of the daily duties required men from each barracks go out on a wood detail to fee the stoves. The ration was two armloads per day per stove. This was good for about one hour, or two half-hour fires. This was the time men could toast their bread slice or warm liquids. In Barracks 24 a man put a canteen full of liquid inside the stove resulting in an explosion and injuring five others. He got five days in the guardhouse. All camp work cleaning out the latrines, trench digging (air raid shelter), snow shoveling, and breaking rocks for walk ways was done by prisoners. “The men volunteered for this work to keep busy and also obtain extra food.” The Geneva Convention allows captors to assign work to men under non-commissioned rank. Work groups were sent out to local farms and infrastructure sites. Non Commissioned officers were required only to perform supervisory work and officers no work at all unless they elected to do so. “Until Pvt. Pfannenstiel became CMOC, German guards just marched into the camp and took the first men: in sight for necessary camp details.” He set up a roster system to assign work and rotated schedules. It was so cold the camp was known as “Little Siberia.” No mail was received and little sent ever arrived in America. Pfannenstiel recalled, “They kept telling us to write home, they would give us paper to write on. It was all used paper, it was blank on one side, but the other side had been used. They gave you an old envelope, one that had already been used, and they would pick them up, but as far as we knew none of them had ever left Germany. They just tried to make us feel better by telling us to write a letter and that they would mail it.” Pete House remembers special letters and cards issued were in French and German, designed so an envelope was not needed. “We were allowed two post cards each week and two letters each month. Perhaps six eventually arrived home.” Trading was a big activity among POWs with cigarettes being the most in demand. Sadly many men traded away food, clothing and personal possessions for smokes. A guard observed one POW to sometimes wear up to three watches on one arm. Trading was also carried out against the rules with other nationals over the fences. The camp was provided with some musical instruments and plans were made for band and theater. Players were found and assigned to the instruments and a choir was formed. House was to be the stage manager. “My foot locker padlock was to be put on the door of our recreation room. We simply went down too fast in health to actually do much about it.” A phonograph player, books and decks of cards were sent over from the British POW hospital, LX C at Bad Soden. Several former journalists started a camp newspaper. The single issue was taken around and read to or posted for the men. Recreational activity declined amid the deteriorating conditions~ The Germans provided de-lousing on two occasions for the men, but never for the barracks. On sunny days men would sit outside and pick the lice from their bodies and clothing only to be re infested again. When men sat around talking, it was not about sex or women, it was about food. House said “The worst things about being a POW was the continuous cold, lack of food and boredom. The daily routine was wake up for the ersatz coffee and roll call, wait for the noon soup, evening bread and ersatz tea, and roll call, then back to bed.” Camp Deaths: A few men quickly lost the will to live. The CMOC Kasten recalled one day the two chaplains came to him for help because one of the boys wanted to die. Hans decided a bit of shock therapy would be used. He asked the POW for his wallet from which Hans took out a picture of his family. He held it in front of his face and told him, “Look you (expletives) if you don’t have the guts to live for yourself, at least have the guts to live for your family.” He died two days later. The second CMOC Pfannenstiel saved a hand-printed document listing 38 men (one English) who died from January 26th through April 1st of 1945 and also recorded them in his personal log. Three of the men died from an accidental air strafing of the camp on February 6th and four were listed as having died at Bad Soden [hospital]. Causes of death were pneumonia, malnutrition, heart, meningitis, diphtheria, and combinations of these. The strafing also killed three Serbians, two French and two Russians. The Red Cross was notified to alert Allied Air Force Groups to the location of the camp. Funerals and burial of American POWs were on a small, steep sloped plot off the compound by a chaplain, pallbearers, witnesses and the CMOC. A typed record was made and a “Personal Articles of Dead” form completed. Other Prisoners: Pfannenstiel recalled, “The French that we had in our prison camp, most of them were trusties they called them. They could go outside of the camp without a guard, and work, and then come back at night. Those guys would sometimes get in touch with the German underground, and pass information. Most of the French didn’t really want to escape, because most of them worked with the underground.” Pete House said one French prisoner got in contact with the American forces in late March and gave accurate information about when the Americans would arrive. The Russian POWs were treated much worse than others. Pfannenstiel said he “felt sorry for them. The Russians couldn’t say a word, or even look cross-eyed at a guard. The guards would beat them where they stood.” German guards said it was because Russia had not signed the Geneva Convention. The daily Russian dead were buried in one open gravesite with additional bodies dumped in. Russian survivors returned to Bad Orb to erect a monument on the site and visit each year. Religion: Regular Catholic and Protestant services were be~d in the camp, with cooperation of the German officers. Some men had prayer books and bibles and others wrote down songs and prayers they remembered. CMOC Pfannenstiel entered religious sketches and prayers into his log. The chaplains were Rev. Samuel Neel and Father Edward Hurley. They helped the medical officers gather medical supplies. Pete House said “it is unreal the stuff some of the men had. Vitamins, aspirin, you name it. This was all put to great use by our doctors.” Among the 349 men sent to Berga, House estimates there were some 80-90 Jews. Nearly the first order of business for the Germans was to identify Jews. House remembers refusing to answer when asked his religion. The interrogator then asked, “how they would know what type of service to provide if I died.” Ernst Beier avoided the transfer to Berga by hiding his Jewish identity through the skillful use of the German language and familiarity with the German culture. Beier was interviewed by a man he felt was a Gestapo agent. Beier was a barracks leader. He credits Hans Kasten as saving his life by also using his knowledge of German to protect Beier in an interview with the same German. He further endured the “questions by some of his fellow prisoners who doubted his authenticity as an American.” Beier was born in Breslau, Germany and got out of Nazi Germany to Switzerland in 1936. He became an American citizen and was sent to the war in Europe. Guards: Men were searched on arrival by guards under the supervision of an officer. In the first weeks of captivity, the Germans tried to get information out of POWs. Interrogations were made particularly of men who were known to understand the German language. German speaking POWs were also used as interpreters. “They had about ten of them (POWs) that they took and they had them strip to the in zero weather, and they had to stand outside until they talked. But they couldn’t get any of them to say anything, and eventually they let them inside after they were about half frozen.” A few of the officers still had strong beliefs about fighting to the end. Some English speaking German officers were educated in the United States and knew the baseball teams and culture of America. The non-commissioned guards were generally older men and a varied lot. One was an attorney in civilian life. They generally were humane and one even risked his personal safety to allow POWs to steal food from the stores on numerous occasions. Another allowed the CMOC to listen to the radio and played cards with him and his staff. Some, seeing the Americans winning the war, became kind to prisoners out of concern for the treatment they might receive from the Americans. Letters were given the friendly guards to prove they had been kind and cooperative to prisoners. Eddie Pfannenstiel received a letter from a former guard in 1946 asking for assistance. He requested chocolate for his children and a copy of the letter of support he had lost. Pat and Oren Windholz established contact with his daughter in 1999 using the address from the 1946 letter. Hans Kasten said a journalist researching the camp for a documentary recently stated that the officer in charge of the camp was tried and executed. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

AMERICAN CHIEF MAN OF

CONFIDENCE The Geneva Convention

rules allowed POWs to select a representative among themselves. For

enlisted men it was the Man of Confidence (MOC). The Germans placed the

word Haupt (Main/Chief/Head) before Vertrauensmann (man of

trust/confidence), hence Chief Man of Confidence (CMOC). Each barracks

elected a leader and the leaders elected the CMOC. Pfc. Johann C. F.

Kasten IV was the first American Chief Man of Confidence. Edmund

Pfannenstiel (second CMOC) was elected a barracks leader and assistant to

Kasten. Both men were chosen because of their leadership on the journey to

camp and partly because they spoke their ancestral German language. Eddie

entered into his log, "J.C.F. Kasten IV was Chief Man of Confidence when

we first came to Stalag IX B was later shipped out with work party." One

archives document states that "Pfc. Kasten was sent out on a kommando

(group) working party." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Memories RICHARD LOCKHART (Remarks at the Holocaust Ceremony, Springfield, IL, April 11, 1991) Some of you know me as a professional lobbyist and indeed I have been one for thirty-two years. However, few know of my personal experience with the Holocaust in Germany during World War II. When the war came, I was eager to be in it, and in fact, enlisted and volunteered for infantry. In due course, I found myself a casualty during the Battle of Bulge. I became a prisoner-of-war. I will not attempt to describe those combat conditions in December of 1944, the “Ardennes Snow March,” four days and nights jammed into box cars with no food or water (and being bombed by our own air force in the process). Suffice it to say, I, along with several thousand other GIs, found myself entering the gates of Stalag IXB, Bad Orb, Germany, on December 26. Stalag IX-B was a very primitive camp, housing several thousand Russian, Serbian and French soldiers. It was reserved for Privates and Privates-First Class only. In the American compound there were no American officers, except a Protestant and a Catholic Chaplain and a dentist. There were no medical facilities, no sanitary services, no heat, and not much grass soup. Men died every day. However, I am not on this program to tell you about my survival under such circumstances, but rather to bring a historical fact to your attention that very few Americans, or anyone else for that matter, know about. Most people believe the Holocaust happened only to European civilians. This is not the case. In Stalag IX-B, U.S. soldiers who were Jewish were, despite our protests, separated from the rest of us. Soon thereafter, they were taken out of the camp, destination unknown. After the war, I learned they were shipped to a slave labor camp — not a prisoner-of-war camp... and few survived. You may wonder how the Germans identified the Jewish GIs. The answer is that they volunteered such fact. Frankly, it is something I have never understood to this day. Was it done as an affirmation of their culture and religion? Was it done out of naiveté? Was it done out of a false sense that because they were American soldiers, ... that would protect them? After forty-six years, I still do not know. What I do know is that it happened. Demonstrating once again the enormous capacity of some to impose the cruelest of punishments on others, solely because of difference in race, religion, nationality, or culture. Those Jewish GIs in Stalag IX-B may have thought they would be exempt from the Nazi Holocaust. They were not, and their fate should never be forgotten. There is an inscription in a World War II cemetery that reads... “When You Go Home, Tell Them of Us and Say For Your Tomorrow, We Gave Our Today.” Thank you for providing me the opportunity to bring to you this historical event for which there are no monuments. There are only the memories. Richard Lockhart |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

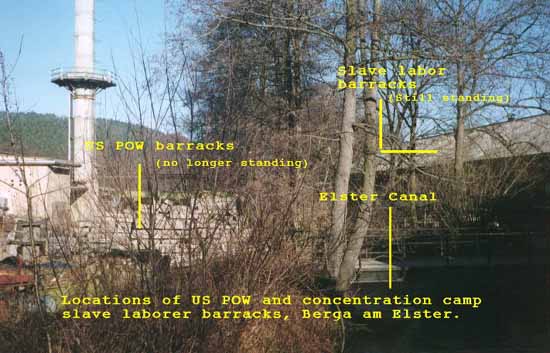

The Soldiers of BergaBy Mitchell G. BardIn 1945, more than 4,000 American GIs were imprisoned at Stalag IX-B at Bad Orb, approximately 30 miles northwest of Frankfurt-on-Main. One day the commandant had prisoners assembled in a field. All Jews were ordered to take one step forward. Word ran through the ranks not to move. The non-Jews told their Jewish comrades they would stand with them. The commandant said the Jews would have until six the next morning to identify themselves. The prisoners were told, moreover, that any Jews in the barracks after 24 hours would be shot, as would anyone trying to hide or protect them. American Jewish soldiers had to decide what to do. All had gone into battle with dog tags bearing an "H" for Hebrew. Some had disposed of their IDs when they were captured, others decided to do so after the commandant's threat. Approximately 130 Jews ultimately came forward. They were segregated and placed in a special barracks. Some 50 noncommissioned officers from the group were taken out of the camp, along with the non-Jewish NCOs. The Germans had a quota of 350 for a special detail. All the remaining Jews were taken, along with prisoners considered troublemakers, those they thought were Jewish and others chosen at random. This group left Bad Orb on February 8. They were placed in trains under conditions similar to those faced by European Jews deported to concentration camps. Five days later, the POWs arrived in Berga, a quaint German town of 7,000 people on the Elster River, whose concentration camps appear on few World War II maps. Conditions in Stalag IX-B were the worst of any POW camp, but they were recalled fondly by the Americans transferred to Berga, who discovered the main purpose for their imprisonment was to serve as slave laborers. Each day, the men trudged approximately two miles through the snow to a mountainside in which 17 mine shafts were dug 100 feet apart. There, under the direction of brutal civilian overseers, the Americans were required to help the Nazis build an underground armament factory. The men worked in shafts as deep as 150 feet that were so dusty it was impossible to see more than a few feet in front of you. The Germans would blast the slate loose with dynamite and then, before the dust settled, the prisoners would go down to break up the rock so that it could be shoveled into mining cars. The men did what they could to sustain each other. "You kept each other warm at night by huddling together," said Daniel Steckler. "We maintained each other's welfare by sharing body heat, by sharing the paper-thin blankets that were given to us, by sharing the soup, by sharing the bread, by sharing everything."

Photo courtesy of Mack O'Quinn"Surviving was all you

thought about," Winfield Rosenberg agreed. "You were so worn down you

didn't even think of all the death that was around you." He said his faith

sustained him. "I knew I'd go to heaven if I died, because I was already

in hell." On April 4, 1945, the commandant received an order to evacuate Berga. This was but the end of a chapter of the Americans' ordeal. The human skeletons who had survived found no cause to rejoice in this flight from hell. They were leaving friends behind and returning to the unknown. Fewer than 300 men survived the 50 days they had spent in Berga. Over the next two-and-a-half weeks, before the survivors were liberated, at least 36 more GIs died on a march to avoid the approaching Allied armies. The fatality rate in Berga, including the march, was the highest of any camp where American POWs were held—nearly 20 percent—and the 70-73 men who were killed represented approximately six percent of all Americans who perished as POWs during World War II. This was not the only case where American Jewish soldiers were segregated or otherwise mistreated, but it was the most dramatic. The U.S. Government never publicly acknowledged they were mistreated. In fact, one survivor was told he should go to a psychiatrist. Officials at the VA told him he had made up the whole story. Two of the Nazis responsible for the murder and mistreatment of American soldiers were tried. They were found guilty and sentenced to hang, despite the fact that none of the survivors testified at the trial . Later, the case was reviewed and the verdicts upheld. Nevertheless, five years after being tried, the Chief of the War Crimes Branch unilaterally decided the evidence was insufficient to sustain the charges and commuted the sentences to time served — about six years. Source: © Mitchell G. Bard. Forgotten Victims: The Abandonment of Americans in Hitler's Camps.. CO: Westview Press, 1994. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Eddie

received two small linen covered books, A Wartime Log, provided by the

Canadian Y. M. C. A. He kept names of his acquaintances in it and a fellow

POW in the camp sketched in scenes of daily life. A third log from the Y.

M. C. A. contained sketches of men he knew, a list of home addresses and a

list of men from Kansas. He kept the official records in the CMOC office

and "stashed some under the floor."

Eddie

received two small linen covered books, A Wartime Log, provided by the

Canadian Y. M. C. A. He kept names of his acquaintances in it and a fellow

POW in the camp sketched in scenes of daily life. A third log from the Y.

M. C. A. contained sketches of men he knew, a list of home addresses and a

list of men from Kansas. He kept the official records in the CMOC office

and "stashed some under the floor."